Everyone knows that Jews have two kinds of heart attacks—"mild" and "massive." From time to time, my Aunt Evelyn, always first with the news, will burst forth with, "Did you hear about Irv? He had a "massive!” Everyone knows that that the missing noun is "coronary." Fortunately, my father's was a “mild.”

My parents had spent the New Year's weekend

in New York, and, at the hotel, my father had experienced some pain in

his chest and arm. When they returned home, he saw his doctor, who discovered

evidence of a heart attack, and prescribed strict bed rest at home. There

were no coronary care units in those days.

My mother asked for the impossible. My sisters

and I had to be good, to be quiet, to stop fighting.

“If you don't keep quiet and stop crying, In kill you,” I responded.

It worked for a few hours, but the bony protuberance of her humerus, bulging forward for all to see, brought down the wrath of my parents upon me.

“You'll be the death of us!”

How many times had those words been spoken in anger! Now they rang loudly in my ears, and I tiptoed around the house, avoiding every confrontation.

I also prayed a lot. As a young child, I had been taught in the Yeshiva, the Orthodox Jewish parochial school that I attended, that one must recite one's prayers daily, upon arising and upon going to sleep. I followed this commandment with the same regularity and fidelity with which I brushed my teeth, lying to my rabbis and dentist about both.

Now. every night, curled up under the covers, I would recite the prescribed prayers in Hebrew with fervor and devotion:

Lying on the floor, I suddenly became aware of my father's breathing behind me. He was a notorious snorer, but this was different. His breath crackled and shuddered irregularly. Later, in medical school, I learned the term “sterterous respiration,” but now, my own chest heaving in despair and disbelief, the words that came to mind were “death rattle.” Perhaps he was only snoring; after all, my sisters took no notice, and continued to be absorbed in the one-toothed dragon on the television screen. No, this was different—it was the malachamovess again, and now he had my father by the throat. Timidly, I stood up and approached the bed. My father lay on his back, his head tilting backward each time he reached for air with his gasping mouth. I nudged his arm, brushed his cheek, then shook both his arms,

“Daddy!” He did not respond.

I wheeled toward my sisters. “Get out!” I snapped.

I raced down the hall toward the den. My mother sat at the desk, bent over the appointment books and records, the weight of a week's stifled worry on her face and shoulders. But she had no right to look tired; she was supposed to keep things like this from happening. And, up to now, everything had gone pretty well.

I stood shaking, unable to speak. Finally, I exploded in anger, pointing toward the bedroom.

“Will you get in there!” I exploded.

As always, my mother understood, and dashed

toward the bedroom. She repeated my strokes and shouts—“Morrie!”—and picked

up the phone.

They came quickly. What good the rubber raincoats

and helmets would do was unclear to me. As they say, “Where's the fire?”

One fireman carried a large apparatus with a mask attached to a hose. Once,

I had seen it in use at the beach at a near-drowning, and I knew its name,a

pulmotor. I knew they would place the mask over my father's face and turn

it on, but what would it do? The motor would pull the breath from him?

I was afraid to watch, and paced nervously in the hallway outside. My sisters

sobbed quietly. In an uncharacteristic gesture, I put my arms around them.

The thought that I might soon become their father-figure filled me with

a physical sense of dread and inadequacy.

My own heart pounding, I re-entered the bedroom. My God! He was alive! And awake! Surrounded by the black rubber firemen, he moved restlessly in the bed. The wetness overwhelmed me. The sheets were damp with the sweat that poured from his face and body.

“I don't want to go to the hospital," he said. (He knew the secret of the Navajo.) These were his last words. His breathing became labored again, and the death rattle returned. The firemen picked up their pulmotor and pushed me outside, or perhaps I ran.

The front door opened, and my Uncle Jack walked

in, carrying his black medical bag. Always cool and in control, he was

the family rock of stability.  Although he had just driven the ten miles across town in just ten minutes,

his serene calm offered the hope that all would be well. He joined the

firemen in the bedroom, and closed the door behind him, I knew what he

would do, I was a devotee of Ben Casey, Dr. Kildare, Martin Arrowsmith

and Rex Morgan, M.D. After all, someday I would be a doctor, too. He would

take a large glass syringe with a long needle and inject adrenaline right

into my father's heart. But what if he missed? Or worse, what if he hit

the mark, and the heart leaked when he withdrew the needle? Would blood

spurt forth from the chest in an unstoppable thin stream?

Although he had just driven the ten miles across town in just ten minutes,

his serene calm offered the hope that all would be well. He joined the

firemen in the bedroom, and closed the door behind him, I knew what he

would do, I was a devotee of Ben Casey, Dr. Kildare, Martin Arrowsmith

and Rex Morgan, M.D. After all, someday I would be a doctor, too. He would

take a large glass syringe with a long needle and inject adrenaline right

into my father's heart. But what if he missed? Or worse, what if he hit

the mark, and the heart leaked when he withdrew the needle? Would blood

spurt forth from the chest in an unstoppable thin stream?

My sisters and I waited in the living room.

A neighbor emerged from the bedroom area. Mr. Falkson and I had had many

meaningful conversations over the years:

“I can take it!” I shouted at him, wrenching from his arm. It was I who would do the comforting, thank you. I put my arms around my sisters, who were crying loudly.

“What are we gonna do?” they sobbed.

“We’ll be OK,” I lamely reassured them.

I felt almost nothing, just a quiet nagging anxiety, but my senses were heightened as never before. I experienced everything with a passionate intensity, but at the same time I was aloof and detached. It was as though I were strolling about on a movie set, interested in the unfolding drama around me, but uninvolved in the action. I watched the firemen return to the truck with their pulmotor. The undertaker's men came, and wheeled something out on a stretcher from the bedroom into their waiting station wagon. What an interesting stretcher it was! It had springs and levers, like an Erector Set, so that you could adjust the height of it. How well-constructed it was! And how nice that they came with a station wagon, and not a hearse, The wagon was a gray Ford--distinguished, but not too funereal—it fit in well in our suburban neighborhood.

The doorbell rang. A plaid-shirted man stood on the stairs, holding a black bag. He explained that he was the doctor-on-call for the fire department. His words drifted toward me on waves of scotch. Thank God for people like him, who offer themselves as targets for our anger in trying times. Thank God for the funeral directors, and customer service representatives, and telephone operators of this world.

“You're too late!” I snapped, and closed the door.

Next came my Zayde, his face its usual

tabula rasa. “Did youmake the brocheh (blessing), Michel?”he

asked.

I looked at him blankly.

“You have to say Boroch davon emes,he reminded me.

Bitterly, I mouthed the strange blessing that

Jews recite upon the death of a loved one, “Blessed be the Just Judge.”

Zayde

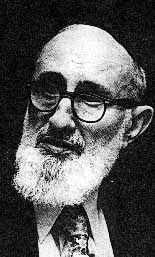

He picked up the telephone and called Rabbi

Soloveitchik, Boston's (some said the world's) leading Orthodox rabbi.

Rabbi Soloveitchik had founded the yeshiva (Jewish parochial school)

that I had attended. His pointed white beard, his dour lined face, and

his gaunt frame draped in a long black coat struck his students silent

with fear and trembling. When he would visit our school to interrogate

the students on their Talmudic studies, the word would pass quickly through

the corridors: “Sely's coming!” Students and teachers alike would wait

in quiet terror at their desks for the Grand Inquisitor to open the door.

His children were my father's patients.

“Gottler,” my grandfather announced himself

into the phone. “Doctor Ingall iz geshtorben.” A silence. "DoctorIngall

iz geshtorben," my grandfather repeated, his voice breaking in mid-sentence

as he related the death of his son-in-law to the rabbi.

Was that a sob from my zayde? A sob?

I couldn't believe it! My zayde, so old, so strong, so impassive.

Ah, that malachamovess! Were there no limits to his power?

My Uncle Israel walked in. He paced with agitation throughout the house, emitting quiet sighs and muffled "Oi”s. He had the same deep grooves from the outer corners of his nostrils to the downturned corners of his mouth as did his brother, my father. Should I comfort him? Shouldn't he comfort me? He seemed to glare at me as he passed. What had I done? I didn't do anything, Uncle Israel!

Uncle

Israel

Uncle

Israel

Suddenly, I knew! I had forgotten to pray! The night before, I had stayed up late, and, having lost the initial panic that my father would die, had fallen asleep without my usual litany of prayer. An empty cavern began to expand in my stomach, and I felt my face turn white. “Please, God,” I begged, “I forgot. You were right to do what You did. Please don't let anything bad happen to family again. I swear (on my father's grave?) that I'll pray to You every night for the rest of my life...Blessed be the Just Judge.”

My cousin Davie sat me down for a fatherly

talk. “I just want you to know what's going to happen tomorrow at the cemetery.”

He was trying to prepare and reassure me, drawing on his own experiences

when his father, my Uncle Louie, had died.

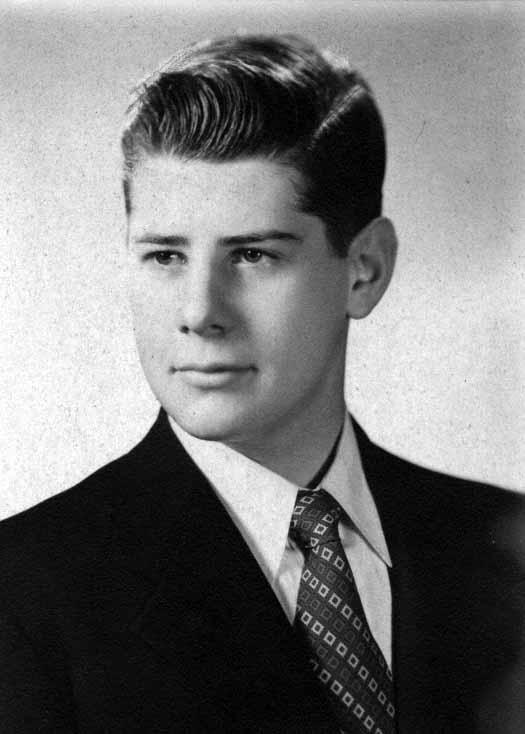

David Ingall

“The worst part is when they bring the casket on this stretcher so it's over the grave, and then this contraption lowers it suddenly into the ground, and it's gone.” That Erector Set that had taken my father from the house. OK, I could handle that.

The next morning, the funeral director came to pick us up to take us to the chapel--in a Cadillac limousine. What a car it was! My first ride in a Cadillac. The upholstery was plush, but I wanted to sit in the jump seat. The thought that it was my first funeral never crossed my mind.

The chapel was packed. Doctor Ingall was a beloved pediatrician, whose friends and patients came by the hundreds. The rabbi's eulogy was a vague drone in my ears, as I gazed at the mahogany casket before me. It was rather like our grand piano, whose lid I liked to raise. Thank God the lid on this one was closed. I tried to picture my father inside, but could not.

At the cemetery, the Erector Set led the procession, then Rabbi Soloveitchik, intoning psalms in a mournful dirge. Seven times we stopped on the path to the grave in accordance with Jewish ritual. As Davie had warned, the Erector Set lowered the grand piano into the ground. I marveled at the feat of engineering

And then they started to throw the dirt. The sound of the hard winter earth falling onto the hollow wood casket was deafening. For this, Davie had not prepared me. I felt my chest heaving, as sobs and wails began to erupt from inside me. A prayer book was thrust before my face. “Say Kaddish, Michel,” my zayde instructed.

I began to recite the prayer for the dead.

I knew it by heart, or thought I did, for the Kaddish is recited

during the daily prayers. But the burial Kaddish was different;

I had never seen it before. The long incomprehensible Aramaic words were

obscured by the tears in my eyes, as I struggled to make sounds other than

sobs.

The Cadillac had lost its thrill on the way

home. A sensation unlike any I had ever felt filled my chest and abdomen.

It was a physical pain, a gnawing emptiness that actually hurt.

At home, it turned to hunger. The traditional dairy meal for mourners had been prepared by friends. All of us were astonished at how hungry we were. We began to devour the hard-boiled eggs and tuna fish salad.

“What's in this tuna fish? It's delicious!” we exclaimed.

“It’s Ritter's Relish," someone said.

We smiled. “Ritter's Relish! It's fantastic!”

We giggled, "I've never had Ritter's Relish!" Tuna fish flecked with bits

of red pepper and tomato sprayed from someone's mouth, and we broke into

uncontrolled laughter.

The shiva week of mourning had begun.

A tall candle in a red glass urn was lit; it would burn for seven days.

Visitors came in an endless stream to pay their respects, entering the

front door without knocking, as was the custom.

I wondered what he would say to me. Perhaps,

"This is what happens when you forget to say your prayers." No, he had

much worse in store for me.

Rabbi Soloveitchik

He gazed at me silently, fingering the short piece of black satin pinned to my lapel. The funeral director had used a scissors to make a short neat incision in it, marking my official debut as a mourner.

"Dos iz nit kayn kriyoh," scowled Rabbi Soloveitchik to my zayde--That is not a valid rending of the garment.”

My zayde told me to put on an old sport jacket. Dutifully, I went to my bedroom and selected a Harris tweed jacket that was a bit too small. No sooner had I donned the jacket, than Rabbi Soloveitchik and my zayde walked in.

"Tear it at the lapel," commanded the rabbi.

I pulled at the thick weave with all my might, but it would not give. Rabbi Soloveitchik seized me by the lapel, and began to tear at the sturdy fabric. Generations of hardy weavers from the Hebrides Islands had prided themselves on the strength and durability of their work, but they had not reckoned with the detemnination and power of Rabbi Soloveitchik. His face became red and contorted as he lifted me off the floor. When he had finished, I looked down at my chest, wondering if the pounding of my heart was visible through the torn tweed lapel. I could feel the sobs mounting again inside, but would not give my assailants the satisfaction of crying in front of them.

"It's time to daven, Michel," said my zayde, :"You can lead the minyan in evening prayers."

“I don't want to,” I mumbled angrily, "You do it." As the assembled mourners and guests droned through the evening services, I resolved that I would never again pray to a God whose representatives dealt so cruelly with me.

But that night, from the silence and loneliness of my bed, I murmured once more, “Please, God, I'll say the Sh'ma every night forever--just don't let anything bad happen to my family again.”

Several weeks later, the Ingalls (now only my mother, Gilda, Nancy, and I) went up to New Hampshire to visit our old friends, the Kaplans. The snow was plentiful in those days, and the there was a big hill to ski down right outside the Kaplans' big white house. I finished a run down the hill and started back up. Suddenly, Gilda was running down the hill, tears in her eyes.

"Michael! Michael!" she shouted, "Come quick! Mommy just fell down the stairs, and she's lying there and she's not moving!"

I ripped off my skis and began running up the

hill as fast as I could. Suddenly I realized--I had stayed up in bed very

late the night before, talking with Elvin, who ws four years older, and

whom I liked and admired so much. I had fallen asleep without saying the

Sh'ma for the first time since my father's death.

"Oh, please, God, please don't let my mother

die.I'm sorry! I won't do it again. It wasn't my fault. I just fell asleep.

I'll never forget to say the Sh'ma again."

Mommy

And then I stopped in my tracks. "What is

this?" I asked myself. "You don't believe in God. Not that kind of a God.

God doesn't make bad things happen or good things happen. They just happen...I

hope my mother's OK." And she was. She was just stunned and had broken

her coccyx.

And so I lost my fear of the malachamovess.

Until he started getting personal.